There are generally 7 major contributors to non-contact injuries acquired performing sporting like activities. They are, in no particular order: Age, injury history, improper warm-up, poor flexibility, posture, muscle strength imbalance and fatigue. Two are these contributors (age and injury history) are non-modifiable, meaning, nothing can be done to change or alter them. We cannot change our age, we can only get older; we cannot change our injury history, if I pulled my hamstring muscles during soccer practice last season, nothing can undo that now.

1. So how does age contribute to injury? The older the athlete, the greater change of incurring a soft tissue injury. The cut-off appears to lie somewhere around 23-25 years old (Yeah I know, that’s not old). So once an athlete hits their mid twenties, regardless of how fit or conditioned they are, all things being equal, their injury risk will be higher then that of their younger counterparts.

2. Secondly, injury-history, previous injury to a joint or muscle automatically increases chances of re-injury. That hypothetical hamstring injury I mentioned earlier, regardless of how diligently I rehabilitate it, my chances of re-injuring my hamstring muscles are higher than if I had never injured them. Same story with ankle sprains, those with previous sprains are at higher risk of recurrence. The other aforementioned contributors to injury (improper warm-up, poor flexibility, posture, muscle/strength imbalance and fatigue,) are modifiable, meaning if addressed properly, their contribution to injury can be lessened or possibly eliminated.

3. I can choose to warm-up properly prior to engaging in sporting activity, or I can ignore it, my choice. Warming up improperly (which includes NOT warming up at all) increases chances of acquiring an injury. Briefly, here’s the recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine: 5-10 minutes of walking, slow jogging, or stationary cycling, followed by dynamic stretches that mimic the movements the athlete will be doing during the workout or competition. Static stretching may be an option for some, power oriented sports participants beware (see my previous blog on this topic here).

4. Posture, poor lumbar posture contributes to hamstring injury, postural defects in the knees and feet have been found to contribute to overuse injuries in the lower extremities.

5. Poor flexibility can contribute to poor movement patterns, limited range of motion which contributes to injury. For example, tight hip flexors can contribute to spinal injury during a bench press, as well as hamstring injury during sprinting.

6. Muscle imbalance, or a the inability of a muscle to absorb or withstand the forces generated by an opposing muscle at the same joint. The agonist muscle generates force at a joint, while the antagonist muscle must contract eccentrically to slow down or “brake” the moving limb to prevent damage to the joint. Examples include – sprinting, hamstrings must be able to withstand forces generated by the quadriceps and hip flexors, throwing, elbow flexors (antagonist) must withstand forces generated by elbow extensors (the agonist). If the antagonist muscle cannot slow the movement down at the end of the action, injury ensues. So muscles working in opposition must achieve a specific balance of strength and flexibility. An imbalance is also used to describe a difference (usually >10%) in flexibility or strength among bilateral muscle groups (for example, muscles in the left leg compared to the same ones in the right leg). When a single limb is considerably stronger than the contralateral (the other side), then risk for injury in the weaker limb increases.

7. Finally, fatigue. Studies looking at leg injuries in soccer players find increased occurrences of muscle strains in lower extremities in the second half of a soccer match compared to the first half. This implicates fatigue is a contributor to these injuries. Additionally, proper form, technique and mental focus can all be negatively affected by fatigued muscles. A sport specific athletic performance assessment and/or a general fitness assessment can often identify asymmetry between opposing muscle groups, as well as postural deficits in hips, knees, and ankles.

Now for the take home lessons:

- Always, always perform a proper warm up prior to sporting activity.

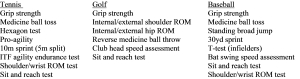

- Consider an appropriate physical assessment to identify muscle/strength imbalances, prior to training and competing.

- Be sure flexibility and core strength are getting attention in your training plan.

- Finally, the importance of proper training and conditioning before participation in competitive sports cannot be overstated. While, for some a sport specific exercise training plan can mean training for weeks or months before participation in an actual competition, it is well worth it in the long run.

Hope this helps and thanks for reading!